THE HOLLYWOOD SQUARETET / PUNK-COMEDY FREEJAZZ

Not one scrap of evidence exists to confirm the truth of any of these claims. But enough facts have emerged through newspaper accounts and painstaking research done by archivist Donald M. Marquis to give us a pretty clear picture. Buddy Bolden may not have single-handedly invented jazz, but he was its first rock star.

Charles "Buddy" Bolden was born in New Orleans on September 6, 1877 to Westmore and Alice Bolden at 319 Howard Street, an address convenient to his father’s work as a teamster. Buddy grew up at various addresses within close proximity to his birthplace, putting him within walking distance of two prominent New Orleans districts: Uptown and the more infamous Storyville. Named for alderman Sidney Story, who on October 1, 1897 drafted legislation to cordon off twenty square blocks of the city to contain prostitution and other unlawful activities.

The Boldens were solid, middle-class citizens of African-American origin who had grown up during the Civil War, an era gladly forgotten by the family. It’s hard to imagine a world of challenge and opportunity amid the chaos of late 19th-century New Orleans, but young Buddy was exposed to a type of cultural renaissance in the city, which was fired by freedom of expression and fueled by music.

New Orleans teemed with a heterophony of musical instruments and players, which included concert bands, dance bands, and funeral bands, which included Blacks and Creoles as well as Irish, Italians and European Jews. Turners Hall, where German brass bands played for weddings and other festive events was within hearing distance of Bolden’s home. Like the “Krewes” which marched in Mardi Gras parades, the Crescent City's early brass bands were social organizations that would stage daylong events, beginning with a street parade and ending with a ball-dance at night.

In the 1880s, the city was wide open to these events, and families of all races participated. But if there was an idyllic phase in young Bolden’s life, it ended abruptly. His sister died of encephalitis in 1881, then his father died in 1883 at age 32, when Buddy was seven years old. Persevering through the decade, Buddy, his mother and his sister Cora witnessed the first changes stemming from the post-Reconstruction era, which introduced segregation to the city.

There is no definitive record of exactly how Bolden became a musician. Some suggest he attended the Fish School for Boys, an experience which would have taught him music in a disciplined manner. Some say it was church, a place where music abounded. In 1894, he had apparently received coronet lessons from a neighbor, who was having an affair with his mother at the time. Embellishing an ordinary fact, like taking coronet lessons, but from his mother’s lover, could make it a tall tale straight from the heart of the New Orleans storytelling tradition.

What is known is that Bolden became a barber, as no man in the city could support a decent living as a musician. Yet by the onset of the Spanish-American war in 1898, Bolden had earned a title, “Kid Bolden,” having played his way as a young sensation into Uptown and Storyville clubs. In those days gigging in New Orleans wasn’t just a routine appearance at dance halls, it was a matter of adherence to social and professional obligations: a musician would play at Miss Cole’s garden parties during the day to secure a gig at night at her popular Josephine Street pavilion at night.

Back at the barbershop on Franklin Street during slow periods, Bolden would rehearse with like-minded musicians in the back room. They were attempting to twist a wide range of tunes, everything from ragtime marches, mazurka waltzes, polkas, gospel and spiritual standards into newly composed blues tunes with a dance beat called "Tin-Tin Type," named for the Tin Type Hall. Originally built for the typesetter’s guild, the Tin Type Hall on Liberty Street in Uptown was rented out to social clubs by a janitor on the condition that they hire the Buddy Bolden Band. Does that make this janitor the first jazz promoter?

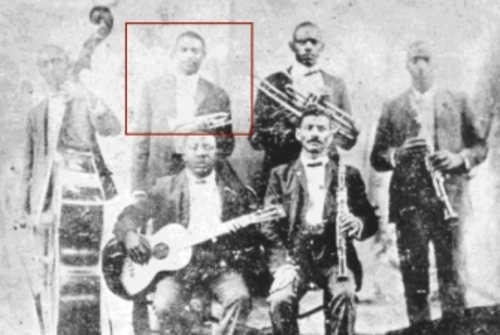

The core members of Bolden's band included, valve-piston trombonist Willy Cornish, clarinetists William Warner or Frank Lewis, drummer Cornelius Tillman, guitarist Brock Mumford, and bassist James Johnson.

In addition to working as a barber and musician, Bolden published a New Orleans gossip sheet called The Cricket, which connected some of the city’s leading citizens to Storyville’s vice and corruption. As backlash to the publication, Bolden’s music was attacked for being loud and lewd. Perhaps this is where his reputation of playing too loud came from. More likely, it stemmed from the fact that brass and other wind instruments of the day were emerging from centuries of reserved use even in marching bands. Playing with volume, in a style which was emulated by descendant horn masters like King Oliver and Louis Armstrong was downright bold.Around the turn of the century Buddy Bolden was crowned the "King" of New Orleans jazz, and was expected by townspeople to appear at every event of significance. Parades, baseball games, ship launchings, political picnics, block parties, which wouldn’t get into swing until he stepped onto the stage. At night, he’d play for carnival masquerade balls, or at Storyville’s red-light district saloons until 11:00 PM. Afterwards, late into the evening he’d appear for the third shift of his 20-hour workday for black dance venues at Perseverance Hall, Jackson Hall, the Odd Fellows Hall, and the Union Sons Hall on Presidio Street.

An old Uptown meeting hall converted into a church, the Union Sons Hall was also called Kinney’s or Kenney’s Hall, and later became known as the "Funky Butt," because of its association with Bolden’s band and one of their hit tunes for which Willy Cornish was supposed to have improvised the lyrics “Funky Butt, Funky Butt, take it away, open up the windows and let the bad air out.” The lyric supposedly captures Bolden's distaste for the pungent odors emanating from sweaty dancers in the tiny hall.Bolden’s band was famous for vulgar lyrics and raunchy rhythms of a medium or slow beat laced with blues. Tunes with immense popularity, predecessors perhaps to pop hits of the future, including Don’t Go ‘Way––Nobody, Ti-Na-Na, which was later recorded by Jelly Roll Morton, Ida, Sweet as Apple Cid’a, and the closing tune, Home Sweet Home, which the band also played for troop ships embarking for the Spanish-American War. One more tune, Get Outta Here, was played at the Funky Butt Hall at 5:00 a.m. sharp.

None of Bolden’s tunes or performances were successfully recorded. Oscar V. Zahn was supposed to have recorded Bolden on an Edison cylinder in 1906. But the cylinder was reported to have burned with Zahn’s family shed in the 1960s, apparently the one and only Bolden recording on earth.

Perhaps it would be prudent to search in the dank corners of the East Louisiana State Hospital, which still stands in Jackson. Bolden began his journey to the insane asylum after he snapped during the Labor Day Parade in 1906. Witnesses insist that he went into a rampage, kicking and screaming his way through the crowd. He hid out with his mother and sister for most of a year, but ended up threatening them after receiving visions. They committed him to the asylum on June 5, 1907.

The music was yet unnamed when Bolden was diagnosed with Dementia Praecox, or schizophrenia. He was never interviewed or recorded after being committed at age 29. He lived there for 24 years before dying alone and forgotten on November 4, 1931 at age 55.

Like every rock star who followed in his footsteps, alcohol, drugs, and women remain the legendary causes of why King Bolden fell from stardom. Yet overwork and struggling with the onset of schizophrenia seem an equally reasonable cause and effect.

Recommended Reading

Non-Fiction:

In Search Of Buddy Bolden: First Man Of Jazz by Donald Marquis, Louisiana State University Press. 1993 (Paperback)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A Comparison of Free Jazz to 20th-Century Classical Music:similar precepts and musical innovations by

© john a. maurer iv

February 24, 1998

The term "free jazz"--coined in 1964 from an Ornette Coleman recording to describe the "new thing" developing in jazz at that time--is even today little understood by jazz musicians and the music community at large. This may be due in large part to the fact that jazz, in general, is very often slighted as lacking in intellectual depth and does not usually receive the same critical analysis granted to the more "serious" art forms. It may also be due to the fact, of course, that improvisation--one of the foundations of jazz--defies traditional analysis in that it is not written out and that not too many scholars are willing to make the extra effort to transcribe music where necessary and to tackle the difficulties inherent in analyzing music based solely on recordings. At the same time, jazz musicians and jazz critics themselves pay little attention to free jazz, as most do not approve of its untraditional techniques to this day and would rather have it not considered jazz at all; rather, they see it as the anti-jazz (Jost, 31). Everything that the traditional jazz musician has practiced years to accomplish and prides himself on, afterall--improvising over chord changes and crafting harmonic complexity, etc.--is suddenly often considered void and a large waste of time. Thus, banished by its own kind and ignored by scholars of serious music, free jazz is something of an orphan in the music community.

A few scholars and critics do take free jazz into their hands, however, and I am very happy to have found the English translation of Ekkehard Jost's Austrian publication of 1974: Free Jazz. Jost, a professor of musicology at the University of Giessen in Germany and president of jazz and new music institutes in Hessen and Darmstadt, does well to address the issues of analyzing an improvisatory art form, cautioning the reader of its drawbacks while also asserting its validity. Not only is the book full of Jost's own precisely notated transcriptions of musical excerpts from a large discography of free jazz recordings, different electro-acoustic measurements made by the author at the State Institute of Musical Research in Berlin also support his claims where appropriate.

To begin with a very general definition of free jazz, then, the only universal "rule" of the style is "a negation of traditional norms"(Jost, 9)--whether it be in harmonic-metrical patterns, the regulative force of the beat, or in structural ideas. Just as 20th-century classical music extends and separates itself from the tonal language of traditional classical music, so too free jazz "frees" itself from the conventions of functional tonality: "In traditional jazz, the primary purpose of the theme or tune is to provide a harmonic and metrical framework as a basis for improvisation. In free jazz, which does not observe fixed patterns of bars or functional harmony, this purpose no longer exists" (Jost, 153). As the "free" in "free jazz" implies freedom from functional tonality and traditional norms, therefore, contemporary classical music, I think, could likewise be aptly labeled "free classical." Both genres, at least, rest on similar precepts.

The absence of a common language in 20th-century classical music and free jazz leads, furthermore, to an inherent "variability of formative principles," the consequence of which is that "specific principles are tied up with specific musicians and groups": "Rudolph Stephan, speaking with reference to avantgarde music in Europe (1969), drew attention to the absorption of the 'musically universal' by the 'musically particular.' This is true of free jazz too..."(Jost, 10). General tendencies and trends in either free jazz or 20th-century classical composition, thus, can only be recognized after thorough analysis and investigation of its constituent parties: "They exhibited such heterogeneous formative principles that any reduction to a common denominator was bound to be an oversimplification" (Jost, 10). This could be a major factor for the fuzziness surrounding free jazz (and 20th-century classical music for that matter, especially outside of academia) as it does not lend itself to very concise explanations or definitions. Traditional: that is what free jazz is not; but as for what free jazz is, one can only answer with respect to individual styles and to general trends. For this reason, Jost divides his analysis into ten chapters--each one dedicated to an important free jazz pioneer or group: John Coltrane (two chapters), Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, the Chicagoans, and Sun Ra.

As well as to its wide variability, a significant factor responsible for the misunderstanding surrounding free jazz, I think, lies in people's misinterpretation of "free." As I have just shown, what "free" does mean in free jazz is "free from tradition" (or, more accurately: "free from functional harmony"); however, this freedom does not in any way further imply that free jazz is "free from everything," or a freedom to do anything. Americans became "free" from Great Britain in 1776, for example, but they did not also become "free" from law: they gained independence from foreign political rule so as to establish their own rules, as realized in the Constitution. So too it is true that free jazz had gained independence from "foreign rules"--i.e. functional tonality--so as to establish their own formative principles (Jost, 13). What is not at work in free jazz, note, is anarchy or unbounded emotionality, as many confuse it to be. Recently, I even read an online hypertext version of an educator's tutorial on jazz improvisation that made the following misleading assertion with regards to free jazz: "There are many different approaches to free playing, but by its very nature, there are no rules" (italics added). This statement falsely insinuates that free jazz means "free from everything." The same tutorial goes on to claim that when playing free music in a solo setting, "you have complete freedom to change the directions of the music at any time, and are accountable only to yourself". On the contrary, free jazz is an intensely communicative--as opposed to self-absorbed--musical genre in which "the members of a group are forced to listen to each other with intensified concentration"(Jost, 23) and in which meaning is created through interaction and not just merely through individual expression or a group of such self-operating individuals.

Neither free jazz nor 20th-century classical music is aimless, then, though often the innocent listener, bred only on traditional music and, thus, listening for things not present in these genres, sometimes cannot understand or hear, therefore, the principles at work behind the music and find it "weird," "senseless," or "bad" sounding. Such criticisms are rather "symptomatic of free jazz as a whole" and stem from the fact that these listeners fail to observe that "divergent formative principles... demand to be heard in various ways"(Jost, 119): or in other words, don't compare apples with oranges--free jazz isn't traditional jazz and it shouldn't be judged or analyzed according to the same criteria. To steal a line from Joel Lester, with reference to analyzing 20th-century music, "to approach a composition with an open mind, ready to discover what the composer has in store for us, is a safer procedure than to assume in advance that any particular pattern will be in evidence" (Lester, 73). "Formative principles are in fact present" in free jazz, much in the same ways that they exist in 20th-century classical music, as we will see, and improvisation in free jazz "is not just left to pure chance": "Analysing a piece that consists simply of accidental sound coincidences would have as little value as trying to calculate the probability of winning or losing in a game of dice where everybody has an equal chance"(Jost, 13).

The comparison between free jazz and concepts of 20th-century classical music, though not investigated in any depth by the author of Free Jazz, is indeed often suggested by Jost himself: "The influences felt in the divergent personal styles of the Sixties encompass musicians like Sidney Bechet, Ben Webster, Thelonious Monk and Lennie Tristano as well as Stravinsky, Schoenberg and Cage" (italics added; Jost, 11), though he often makes the reservation that such similarities are not direct influences: "It would be highly unlikely that anyone would seriously call Sidney Bechet or John Cage 'pioneers' of free jazz"(Jost, 11), and: "The appearance of [Cecil Taylor's] kind of 'collective composition,' at the time that aleatoric techniques were on the rise in European New Music, is surely a coincidence" (italics added; Jost, 76). It is shown sometimes, however, that a few of the pioneers in free jazz did study or have a knowledgeable background in 20th-century classical music: Cecil Taylor studied for three years at the New England Conservatory, for example, where he came into contact with the works of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, and was especially interested in Bartók and Stravinsky (Jost, 66); and Anthony Braxton had made detailed studies of John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen (Jost, 167).

Whether the similarities between the two genres are consequences of each other or not, however, a comparison between them does seem to suggest itself rather loudly. My goal is simply to make the comparison more explicit, using my knowledge of 20th-century classical music and examples that I have heard and studied, to function as sort of a companion essay to the text of Free Jazz itself: an "appendix," say. Such a comparison is thought to be good since it brings together the concepts presented in Free Jazz in an organized manner and can help make the unknown more familiar through association, legitimizing, hopefully, the genre of free jazz to those of music academia unfamiliar with the genre or prejudiced against it, while also hopefully inspiring readers to explore the genre further in their own listening and study.

Before taking a closer look at the similarities, however, I think it is valuable that I first give a quick glance at what the fundamental differences between free jazz and 20th-century classical music are, so as not to confuse the ensuing comparison with an equation. What creates the boundary between jazz and classical music? One obvious difference, already touched upon, is the method of creation: whereas classical musicians put their ideas into written scores--even when utilizing chance processes, free jazz musicians create primarily through improvisation. Another segregating factor between free jazz and 20th-century classical music are their rhythmic characters: "The decisive criterion [of jazz music]--as always--is the rhythmic substance, which despite freedom from tempo and absence of recognizable accentuation patterns [as often can be found in free jazz] still has that psycho-physically sensible kinetic energy that corresponds, however remotely, to the phenomenon of swing"(Jost, 198). Thus, in free jazz--whether directly accentuated or indirectly implied by periodic swells of dynamic and texture--there is always a sense of pulse that underlies the music.

These boundaries, of course, are not always clear cut, and sometimes the genres can become rather indistinguishable. This can occur, for instance, when all rhythmic substance is abandoned in free jazz: "When even an intimation of a common rhythmic basis is dispensed with, kinetic energy is totally reduced and there is a subjective indeterminacy, like that occasionally encountered in serial music... "(re: Cecil Taylor; Jost, 73). Another way that boundaries can become fuzzy is when the methods of creation in either genre are combined, as in the music of Cecil Taylor, which often possesses a "fusion of constructive planning and improvisatory creativity"(Jost, 77) and in the "spontaneous composition" of Don Cherry, which derives its improvisation mostly on pre-constructed thematic catalogues. This sort of fusion can also be found in the classical spectrum in the spontaneous compositions of Luigi Nono and others involved in advanced European improvised music.

My plan of attack in comparing the concepts of free jazz with 20th-century classical music will first entail an analysis of the methods through which either genre extends and abandons the tonal language and its functional harmonies. Next, the different means of expression in free jazz utilized in the absence of functional tonality will then be considered, followed by an analysis of the new approaches to overall formal structure used to encapsulate these means of expression--which, as is also often true of 20th-century composition, are merely extensions of traditional forms. Lastly, I will show how asymmetry and disjunctedness--prevalent tendencies in many aspects of 20th-century classical music--are also characteristic of free jazz in various ways, and how the use of parody, too, is a prominent feature to both genres

Å@

Å@

THE HOLLYWOOD SQUARETET / PUNK-COMEDY FREEJAZZ

CONTACT SOME SQUARE / JASS - JAS - JAZZ...A HISTORY / FRONT PAGE REVIEWS PHOTOS / CERTAIN SQUARES -MORE PHOTOS

Below: BUDDY BOLDEN BAND // Click photo for a history of word origins of "JAZZ " ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------"Dat Funny Jas Band" -1917, the first jazz on record? COLLINS & HARLAN , Comedy Vocal Duo (Bass & Baritone, 1902-1926) By Tim Gracyk

The verse and chorus of "That Funny Jas Band from Dixieland" cite several characteristics of jazz. The music is said to feature "queer" harmony. The rhythm marks the musicians as "mad," or crazy. The music is said to be perfect for wild dancing (the tradition of sitting for the purpose of listening to jazz came much later--the music originally provided new dance rhythms).

The lyrics suggest that jazz is a music for the uneducated working class--specifically, the black working class. In the song, payday arrives. Henry brags about "a roll of money" and invites Mandy to a cafe "full of pep and ginger." Jazz works as an aphrodisiac on this spooning couple, with each one declaring by the end to be charmed by the other as well as by the band. Here is the chorus that follows the first verse:

Oh honey dear,

I want you to hear

That harmony queer

When you listen to

Mad musicians playing rhythm

Everybody dancing with 'em

Hold me close in your arms

I'm in love with your charms and

Dat funny jas band from dixieland

Comic dialogue follows the chorus, with Byron Harlan playing the female in minstrel show fashion. He asks a question that musicologists have tried to answer for years:

HARLAN: "Say, Henry, what is a jas band?"

COLLINS: "Why, a jas band am essentially different from the generalities of bands."

HARLAN: "In what particularity, Henry?"

COLLINS: "Oh, in many ways, Mandy. Now, for instance . . . " [A slide trombone roars]

HARLAN: "Lordy, lordy! Is that one of the ways?"

COLLINS: "Uh-huh. And another is . . . " [Clarinets play]

HARLAN: "Is there any more, Henry?"

COLLINS: "Oh yes, and it goes something like . . . " [Drum roll, bugle call, crashing of cymbals]

HARLAN: "Well, I must say, Henry, your explanation am lucidiously comprehensible!"

COLLINS: "And does you like the jas band, Mandy?"

HARLAN: "Ah sure do."

COLLINS: "Then we'll sing some more."

Singled out as jazz instruments are trombone, clarinet, drum, cornet, and cymbals. No suggestion is made that improvisation or solos taken by individuals were defining characteristics of the music. At one point the singers step away from the recording horn so studio musicians can play momentarily. We hear early jazz! The interlude is a little wilder for Edison--a little hotter--than for Victor (the Victor interlude actually employs slide whistles, with the two singers making noises in the background). Played by an Edison studio band, this musical interlude on cylinder and Diamond Disc is arguably the first jazz on record.

BUDDY BOLDEN JAS BAND

Collins And Harlan

"Jass" in 1916-1917 and Tin Pan Alley

By Tim Gracyk

The Original Dixieland Jazz Band (ODJB), a group of white New Orleans musicians, was the first ensemble to make a jazz recording. The band's "Dixieland Jass Band One-Step" and "Livery Stable Blues" (18255), recorded for the Victor Talking Machine Company on February 26, 1917, in the company's New York City studio, were coupled on the first jazz record. When issued in the spring of 1917, it was a new type of record. Nothing like this had been issued before, and this disc was among the most influential records ever made. It sold very well, with young people across America excited by this new dancing music. Many imitators made records within months, hoping to duplicate the ODJB's success.

New Orleans musicians may have recorded jazz on a cylinder machine in homes before 1917. Many Edison machines from the turn of the century had recording devices that allowed the machine's owner to make recordings on blank cylinders. In other words, some Edison models were like cassette machines of that era, allowing anyone to record anything. But no such recording is known to exist.

Freddie Keppard, a superb African-Ameircan trumpet player who made jazz records in the 1920s, made claims late in his career that he had been invited by a record company (or two or three?) to make records before 1917 or so. Obviously he did not make records this early--again, the white ODJB musicians were the first jazz musicians to attend a recording session. Keppard famously claimed that he turned down the offer (or was it offers?) because he did not want anyone to study the records in order to imitate his style. But no evidence has surfaced collaborating Keppard's bold claim. No memo has surfaced from any record company indicating that Keppard had been invited to record. It may have been a case of sour grapes. Keppard was probably miffed that others had popularized jazz on records, and his response was to say, "Hey, I could have made records, but I just did not want to--I was too good for that!"

There is no doubt about it: in February 1917 the ODJB members were the first jazz musicians to make records (they were also the first musicians, it seems, to identify themselves as "jass" musicians). Some books claim that the ODJB had cut two titles for Columbia weeks earlier, on January 30 or 31, 1917, with Columbia then delaying the release. However, this is a myth. Jazz discographer Brian Rust wrote in the publication Needle Time (July 1987) about evidence suggesting that the ODJB recorded for Columbia later than what Rust had erroneously reported in his own jazz discography. The ODJB made the Columbia record months later than the reported January date. Columbia's own recording logs indicate that the ODJB did not record for the company until long after the Victor recording session. Additional evidence has come to light, notably a document in the hands of a descendant of ODJB member Eddie Edwards. It establishes that the ODJB visited Columbia's A & R man A. E. Donovan on January 30 (not 31, as usually reported) only to audition, not to make a record. Months later, the ODJB returned to Columbia to make a record. The band by this time was in a legal dispute with Victor, so the band members were happy to visit Victor's chief competitor to make a record.

We cannot know how closely that first jazz record--again, a Victor disc--made by the ODJB in late February 1917 resembled the jazz played by black musicians in New Orleans at that time, but it is one valuable source among many that helps us understand the roots of jazz. We simply have no way of knowing how the music played by black New Orleans musicians sounded in the early days of jazz. (They did not call themselves "jass" or "jazz" artists, by the way. The ODJB popularized the words "jass" and "jazz." We must at least entertain the idea that at least some black New Orleans musicians bought ODJB records--as did many other Americans!--and were influenced by the records.)

Again, the ODJB's first records are essential sources for anyone interested in the roots of jazz. Other sources include written and spoken testimony of musicians who, earlier in life, had played in New Orleans in the early years of the century as well as their recordings made from 1922 onwards (records made in the World War I era by non-New Orleans black bandleaders such as Jim Europe, Wilbur Sweatman, and W.C. Handy do not help; Kid Ory was the first black musician from New Orleans to record jazz, in June 1922). A recording like Freddie Keppard's "Stockyard Strut," recorded in 1926, is important since Keppard had been playing jazz long before he make a record. Photos of bands that went unrecorded are duplicated in various books, including A Pictorial History of Jazz by Orrin Keepnews and Bill Grauer.

One rich source for understanding early jazz--how it was played, how people at the time viewed jazz--is overlooked by jazz scholars. I refer to Tin Pan Alley tunes of the day. James Lincoln Collier is a rare jazz historian who acknowledges that popular songs referred frequently to the music during this formative period. On page 97 of Jazz: The American Theme Song, he writes that jazz by as early as 1917 had become a fad, a craze. Performers everywhere were slapping the word "jazz"--or "jaz," "jasz," or "jass" as it was variously spelled--on any kind of production that would even vaguely support the title.

Collier lists seven songs with variations of "jazz" in the title. Of these, I suspect record collectors are most familiar with Marion Harris's version of "When I Hear That Jazz Band Play." Collier states, "All of these songs were published by mid-1917." It is analogous to a slightly earlier trend of automatically adding "blues" to titles.

We can look earlier than mid-1917. The earliest recorded song to refer to jazz is "That Funny Jas Band from Dixieland," copyrighted on November 8, 1916. Cut by the popular comic duo Collins and Harlan (baritone Arthur Collins and tenor Byron G. Harlan), it was issued on Victor 18235. This is so close to the ODJB's first record for Victor (18255--a mere 20 numbers later) that one can almost envision Collins and Harlan passing Nick LaRocca and Larry Shields in the halls outside Victor's New York City studio (the recording artists would not have met, really--they worked in very different professional spheres). In fact, Collins and Harlan recorded the song for Victor on January 12, 1917, weeks before the ODJB's studio debut.

Collins and Harlan had recorded the same song for the Edison company earlier. Different takes were cut on December 1, 1916. One take was issued on Blue Amberol dubbing 3140 in April 1917 and takes were also issued on Diamond Disc 50423 in June (the time between the recording of an Edison item and its release was often long). I find the word "jas" on the rim of my Blue Amberol. I know of no earlier record to use any form of the word "jazz." As I will discuss, the spelling of "jas" is noteworthy. I also own Diamond Disc versions, and listening to the different takes is interesting--variations in the artists' patter can be heard.

Tin Pan Alley songwriters recognized a market for songs about jazz before the first jazz record was even made and before a market for jazz records materialized. Lyricists satirized jazz before jazz was recorded! If we had to characterize jazz by the lyrics of this particular comic duet, we get a sense of jazz that shares little with characterizations made by modern writers defining jazz as an art form. Obviously we cannot rely on popular song writers for our understanding of history nor for defining an art form, but the lyrics of this particular song shed light on how the public in early years perceived this new and "funny" music from "dixieland."

The lyrics were penned by the prolific but then-obscure Gus Kahn. He later wrote words for "Carolina in the Morning" (1922), "Yes Sir, That's My Baby" (1925), and numbers for the 1929 Broadway show Whoopee, among many other hits. Henry Marshall provided the melody. He had several big hits in the 'teens. In 1912 he had published his melody for "Be My Little Baby Bumble Bee," which record collectors now associate with Ada Jones and Billy Murray, who sang the number as a duet for Victor.

The title alone--"That Funny Jas Band from Dixieland"--hints at what was associated with jazz in late 1916. The music was recognized as originating from New Orleans, or at least from the South ("dixieland"). The band playing the music is called by the lyricist a "funny jas band." The music was "funny" in two ways, as lyrics make clear: it sounded odd and it provoked mirth. To put it another way, the harmonies were strange and the music was joyful.

It is easy to forget that jazz was originally a "happy" music despite chords and progressions shared with blues. The music became a somber art only in later decades as jazz musicians became more self-conscious as artists and disdained the traditional role of entertainer. In this song, jazz is characterized as having "lots of pep and ginger." Similar phrases occur in other early songs about jazz. Billy Murray sings of "ginger and pep" in the 1919 "Take Me To The Land of Jazz" (Columbia A2766) as does Bert Harvey, who sings the song on Edison Diamond Disc 50583 and Blue Amberol 3837 (listen for the jazz band interlude). This 1919 song credits Memphis for developing "the jazzy melody":

It was down in Tennessee

That the jazzy melody

Originated

Then waited

For popularity

Now in every cabaret

It's the only thing they play

I love to hear it

Must be near it

That's why I say

Take me to the land of jazz

Let me hear the kind of blues that Memphis has

I want to step

To a tune that's full of ginger and pep

The spelling "jas," which is on all Collins and Harlan renditions of the tune, is worth exploring. Dropping one "s" from the Collins and Harlan title solved a problem for those safeguarding decency in language. H. O. Brunn explains in his 1960 book The Story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band why "jass" did not suit the ODJB when the band enjoyed success: "LaRocca avers that the word 'jass' was changed because children, as well as a few impish adults, could not resist the temptation to obliterate the letter 'j' from their posters." Brunn's book has major errors, and we cannot be certain this is why the spelling changed. It is not a book that can be relied upon, unfortunately.

The first Victor disc of the ODJB features the rare "jass" spelling as does the Columbia issue of the ODJB's "Darktown Strutters' Ball" coupled with "Indiana." Soon afterwards--by mid-1917--the band used the "jazz" spelling. In short, the spelling of this new music's name was uncertain in late 1916 and early 1917. "Jas" is pronounced as "jazz" by Collins and Harlan. The word existed orally before spelling had been established.

I suspect "jas," as used on the Collins and Harlan disc, could have stuck as a name for this new music had the Victor Talking Machine Company persisted in using only these three letters. I realize the spelling which we recognize as standard ("jazz") was already established in some quarters. As early as 1913 a column in the San Francisco Bulletin had analyzed the new term "jazz" (the unnamed columnist did not connect the word with music--Jim Godbolt reprints the column in his 1990 book The World of Jazz). However, the Victor Company played such an important role in making the new music available that had the company continued spelling the word as "jas," others in the industry might have followed suit.

The Edison company used different spellings before finally adopting "jazz" as the spelling. Ron Dethlefson informs me that "jass" was transformed to "jazz" beginning in the October 1917 issue of Amberola Monthly, the Edison trade publication. He finds that his copy of "When I Hear That Jazz Band Play," performed by Jaudas' Society Orchestra, originally had the word "jass" but "zz" was engraved on top of the "ss," which means the Edison Company went to some trouble so that titles on cylinders had the newly adopted spelling! I do not know if this is true for all cylinders at this time mentioning the new music.

"That Funny Jas Band from Dixieland" is sung by Collins and Harlan in the tradition of "Bake Dat Chicken Pie" and other numbers made popular by the duo around this time, especially in preceding years (the duo's popularity went in rapid decline after "jass" caught on). There is singing, an exchange of dialogue, and more singing. These white singers use black dialect, which some people today may find demeaning, but at least in this song the implication is that blacks originated and enjoyed jazz. Full credit is being given to blacks for this new music, however tasteless the delivery may strike some listeners.

The song shares much with earlier songs about ragtime bands. In early 1915 Arthur Collins recorded "Ruff Johnson's Harmony Band" (Columbia A1675), later covered by Gene Greene for Victor (#18266). Collins and Harlan in 1915 also recorded Will D. Cobb's song "Listen To That Dixie Band" (Columbia A1850), covered for Edison by Irving Kaufman:

Listen to that big brass band

From my home in dixieland

That's the band I love best of all

Everybody will fall for the old bugle call

Listen to that big bass drum

Ain't that trombone goin' some?

Oh boy! What is it they're playing?

Oh joy! That's got 'em all swaying?

Hurry for the clearing

Hear the darkies cheering

For that big sweet band

The word "jazz" is not used but in these songs we can sense popular music evolving towards jazz. Lyrics celebrate brass bands from dixieland that played syncopated melodies. Irving Berlin's 1911 "Alexander's Ragtime Band" is a prototype--even here Collins and Harlan played a part, deserving much credit for popularizing the tune since their Victor recording of it (16908) was among the best-selling discs of that decade (Eddie Morton's "Oceana Roll" on the other side did not hurt sales). Their Columbia version also sold well. Berlin's tune was perhaps the most successful of these songs celebrating brass bands but it was not the first of the genre. For example, a year earlier Collins and Harlan had recorded "When Mose Leads the Band" (Columbia A814).

In 1914 the Peerless Quartet recorded "Follow Up The Big Brass Band" (Columbia A1532), with Arthur Collins joining others in praising brass bands. Lyrics in most of these songs credit the cornet player with generating the most excitement--we are not far from the reverence with which Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke were held by the next generation of music lovers (analogous today is the revered guitar soloist in rock music). Listen also to Arthur Fields' "Everybody Loves a 'Jass' Band" on Edison Diamond Disc 50439 and Blue Amberol 3197 for references to the cornet and even for an early jazz piano solo.

Although I cannot cite here all recordings from 1917 that mention "jazz," I can list a few I have listened to while preparing this article. One is "Mr. Jazz Himself," recorded by Irving Kaufman for Columbia (A2460). Prince's Band recorded the same "Mr. Jazz Himself" (Columbia A2370) in August and had recorded, months earlier (in June), "Everybody's Jazzin' It" (Columbia A2347) and "New Orleans Jazz" (Columbia A5983). Earlier still is the April recording by Prince's Band of "Hong Kong" (A5967), called a "Jazz One-step."

One Columbia disc from 1917 has titles of interest on both sides: "Alexander's Got A Jazz Band Now," which was Gene Greene's final recording (A2472), and "Cleopatra Had A Jazz Band," sung by tenor Sam Ash. Prince's Band was later to cover "Cleopatra Had A Jazz Band" in December of 1917.

The "Jazz One-step" recorded by the Rudy Wiedoeft-led Frisco "Jass" Band (the song is also known as "Hong Kong") was the first jazz instrumental released by Edison. It appeared as a Blue Amberol (3228) in August of 1917. Edison recordings have been unjustly ignored by jazz historians.

The last line spoken by Arthur Collins ("Then we'll sing some more") suggests singing is appropriate in this cafe featuring a jazz band, but there is no way to argue that these two seasoned performers were the first jazz singers. On the other hand, Collins as a solo artist cut "That Funny Jas Band From Dixieland" for various small record companies throughout 1917, and it is possible that he played with the melody in significant ways (these records-- Operaphone, for example--are incredibly rare). It is enough that we remember Collins and Harlan for celebrating jazz on record even before jazz itself was preserved on shellac.

© 2006 Gracyk.com

Photo: Collins and Harlan // Click for some you tubed music.

Å@